The Tree of Life – When do Plants spin off new Species?

An international multi-disciplinary research team from Brown University, the Heidelberg Institute for Theoretical Studies, and Yale University has reconstructed the largest evolutionary tree (phylogeny) for plants and learned that major groups of plants tinker with their design and performance before rapidly spinning off new species. The finding upends long-held thinking that plants’ speciation rates are tied to the first development of a new physical trait or mechanism. The U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF iPlant initiative) and the German Science Foundation (DFG) funded the research.

Providence, RI [Brown University]/Heidelberg, Germany [Heidelberg Institute for Theoretical Studies]/New Haven, CT [Yale University] — Evolution has been successful for billions of years and produced a vast amount of successful new species, but we still do not understand the underlying mechanisms. Researchers from the U.S. and Germany have recently unraveled new parts of this process. They found that plants initially tinker with their configuration and performance prior to coming up with new, improved versions of themselves.

The issue at hand is when a grouping of plants with the same ancestor, called a clade, begins to spin off new species. Biologists laboring over assembling the tree of life have long assumed that rapid speciation occurred when a clade first developed a new physical trait or mechanism and had begun its own genetic branch. But the team, led by Brown post-doctoral researcher Stephen Smith, who is also affiliated to the Heidelberg Institute for Theoretical Studies (HITS), discovered that major lineages of flowering plants did not begin to rapidly spawn new species until they had reached a point of development at which speciation success and rate would be maximized. The results are published in the American Journal of Botany (2011; 98 (3): 404 DOI: 10.3732/ajb.1000481).

Evolution is not what we previously thought,” said Smith, who works in the laboratories of Brown biologist Casey Dunn and of HITS computer scientist Alexis Stamatakis. “It’s not as if you get a flower, and speciation (rapidly) occurs. There is a lag. Something else is happening. There is a phase of product development, so to speak.”

Research in this area is only possible with computational methods. “This is a nice example of how computer science and cyberinfrastructure initiatives can help to extend the limits of biological explorations” says Alexandros Stamatakis, group leader of the scientific computing group at HITS (Heidelberg).

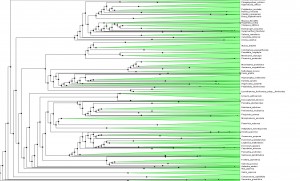

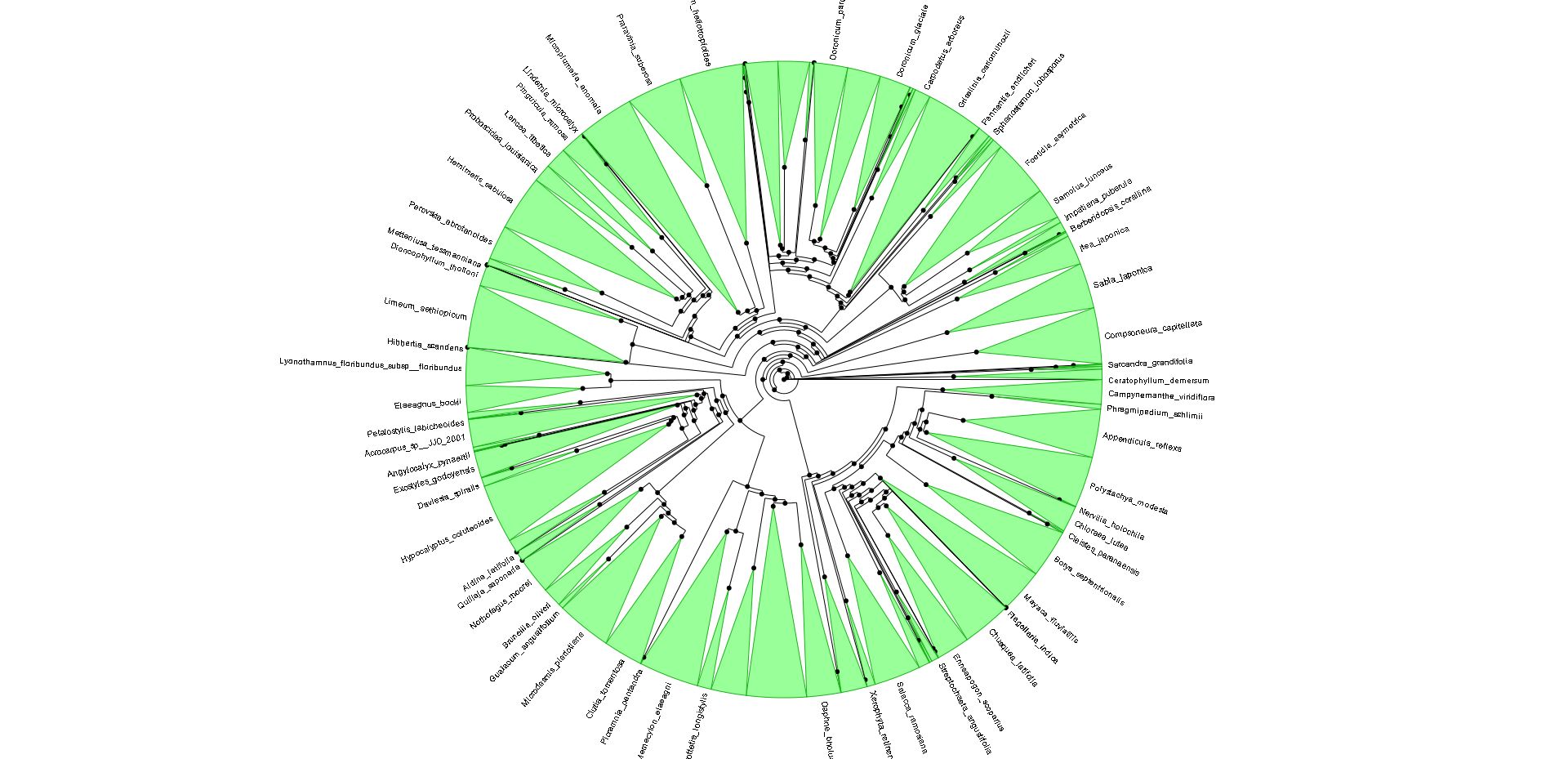

To tease out the latent speciation rate, Smith and co-workers computed the largest plant phylogeny (evolutionary tree) to date, involving 55,473 species of angiosperms (flowering plants), the genealogical line that represents roughly 90 percent of all plants worldwide. Reconstructing a tree of this size is also a technical milestone and a starting point for many other studies. The researchers looked at the genetic profiles for six major angiosperm clades, including grasses (Poaceae), orchids (Orchidaceae), sunflowers (Asteraceae), beans (Fabaceae), eudicots (Eudicotyledoneae) and monicots (Monocottyledoneae). Together, these branches make up 99 percent of flowering plants on Earth.

The common ancestor for the branches is Mesangiospermae, a clade that emerged more than 125 million years ago. Yet with Mesangiospermae and the clades that spun off it, the researchers were surprised to learn that the boom in speciation did not occur around the ancestral root; instead, the diversification came about some time later, although a precise time remains elusive.

“During the early evolution of these groups,” Smith said, “there is the development of features that we often recognize to identify these groups visually, but that they don’t begin to speciate rapidly until after the development of the features.”

Put another way, the authors write, “These findings are consistent with the view that radiations tend to be lit by a long ‘fuse,’ and also with the idea that an initial innovation enables subsequent experimentation and, eventually, the evolution of a combination of characteristics that drives a major radiation.”

Shifts in diversification aren`t often directly associated with the origin of the familiar group (orchids, sunflowers, etc.). There are many more shifts than one might imagine. The diversity patterns may be explained not just by a few major shifts, associated with the major groups, like flowering plants. Instead, the diversity of groups more likely reflects a composite of many individual, smaller bursts within clades. It wouldn´t be possible to see this very well in the context of small phylogenies.

Smith believes some triggers for the speciation explosion could have been internal, such as building a better flower or learning how to grow faster and thus outcompete other plants. Or, the winning edge could have come from the arrival of pollinating insects or changes in climate. The team plans to further investigate these questions.

“Taken at face value, our analyses suggest that many bursts in speciation, spread quite evenly and hierarchically across the entire tree, are responsible for the evident success of the flowering plants,” explains Jeremy Beaulieu (Yale).

Michael Donoghue (Yale) adds: “The possibility of working with phylogenetic trees of this size opens up all sorts of new research questions, but also clearly highlights the need for new statistical and computational tools. This area is in its infancy.”

The U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF iPlant initiative) and the German Science Foundation (DFG) funded the research. The computations to assemble the phylogeny were performed at Yale’s High Performance Computing Center and at the Texas Advanced Computing Center.

The tree can be browsed online at: http://portnoy.iplantcollaborative.org (select BigPlantTree) thanks to resources provided by the NSF iPlantCollaborative and the efforts by Karen Cranston at the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center.

Link to the article in the American Journal of Botany:

http://www.amjbot.org/cgi/reprint/ajb.1000481v1

Press Contact:

Dr. Peter Saueressig

Public Relations

HITS Heidelberg Institute for Theoretical Studies

Tel: +49-6221-533-245

Fax: +49-6221-533-198

peter.saueressig@h-its.org

www.h-its.org

Charles “Robin” Hogen

Director of Strategic Communications

Yale University

O:203-432-5423

C:203-856-8115

robin.hogen@yale.edu

Richard Lewis

Physical Sciences Writer

Brown University

401-863-3766 (w); 401-527-2889 (m)

richard_lewis@brown.edu

www.brown.edu

Scientific Contact:

Dr Stephen Smith

Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology

Brown University

stephen_a_smith@brown.edu

Dr Alexandros Stamatakis

Scientific Computing group

Heidelberg Institute for Theoretical Studies (HITS)

Tel: +49-6221-533-240

Alexandros.stamatakis@h-its.org

Prof Michael J Donoghue

Sterling Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology

Yale University

Office phone: (203) 432-2074

Fax: (203) 432-5176

michael.donoghue@yale.edu

About HITS

HITS, the Heidelberg Institute for Theoretical Studies, was established in 2010 by physicist and SAP co-founder Klaus Tschira (1940-2015) and the Klaus Tschira Foundation as a private, non-profit research institute. HITS conducts basic research in the natural, mathematical, and computer sciences. Major research directions include complex simulations across scales, making sense of data, and enabling science via computational research. Application areas range from molecular biology to astrophysics. An essential characteristic of the Institute is interdisciplinarity, implemented in numerous cross-group and cross-disciplinary projects. The base funding of HITS is provided by the Klaus Tschira Foundation.